Immigration and Schools: Understanding Evolving Policies

Click here to download the article in pdf format.

This present administration has brought about a number of changes regarding undocumented people in the United States. Children and, therefore, schools have not been spared from the impact. Some of these issues are the product of new policies, while others are the result of how this current government enforces or declines to observe the norms of previous administrations. Here, we outline several of the major matters of concern for school entities surrounding this issue, and possible responsive strategies.

First, as an introductory perspective, it may be helpful to share a foundational case related to undocumented children and schools. Plyler v. Doe, 457 U.S. 202 (1982), struck down a Texas statute denying public education funding for children not “legally admitted” into the United States. The court held that this violated the Equal Protection Clause of the Fourteenth Amendment, because people are “persons” regardless of whether they have citizenship. In effect: students of any status have a constitutional right to education.

The current administration has issued several executive orders that run somewhat contrary to that case:

Executive Order 14159, "Protecting the American People Against Invasion," expanded immigration enforcement by increasing federal agents, denying funding to "sanctuary" jurisdictions, and maximizing the use of expedited removals.

Executive Order 14160, "Protecting the Meaning and Value of American Citizenship," aimed to redefine birthright citizenship by instructing federal agencies to deny citizenship documents to children born in the U.S. to certain non-citizen parents (although it is currently facing legal challenges).

Executive Order 14161, "Protecting the United States From Foreign Terrorists and Other National Security and Public Safety Threats," mandated a review of immigration vetting and screening procedures to prevent the entry of individuals deemed a threat to national security or public safety.

It’s important to note that Executive Orders do not overrule Plyler, enforcement of any new standard can always be the target of a private cause of action, such as Issa v. School District of Lancaster (2017) and more recently T.R. v. School District of Philadelphia, No. 20-2084 (2021), and, above all, it is always advisable to follow the actual law.

Interaction with United States Immigration and Customs Enforcement (ICE)

The “Sensitive Locations Policy” of previous administrations, which put schools, religious institutions, and hospitals “off limits” to ICE investigations and raids, has been rescinded. Some examples of ICE actions in 2025 include a student in Massachusetts being arrested on his way to volleyball practice, an ICE raid in Denver that delayed buses from departing from a school building, and attempted arrests at a school building in Los Angeles which were thwarted by administration.

Practical Policies

Districts should not ever ask for SSNs or citizenship/Green Card/immigration status.

The undocumented status of a child or parent should not be recorded by the school in any files or notes.

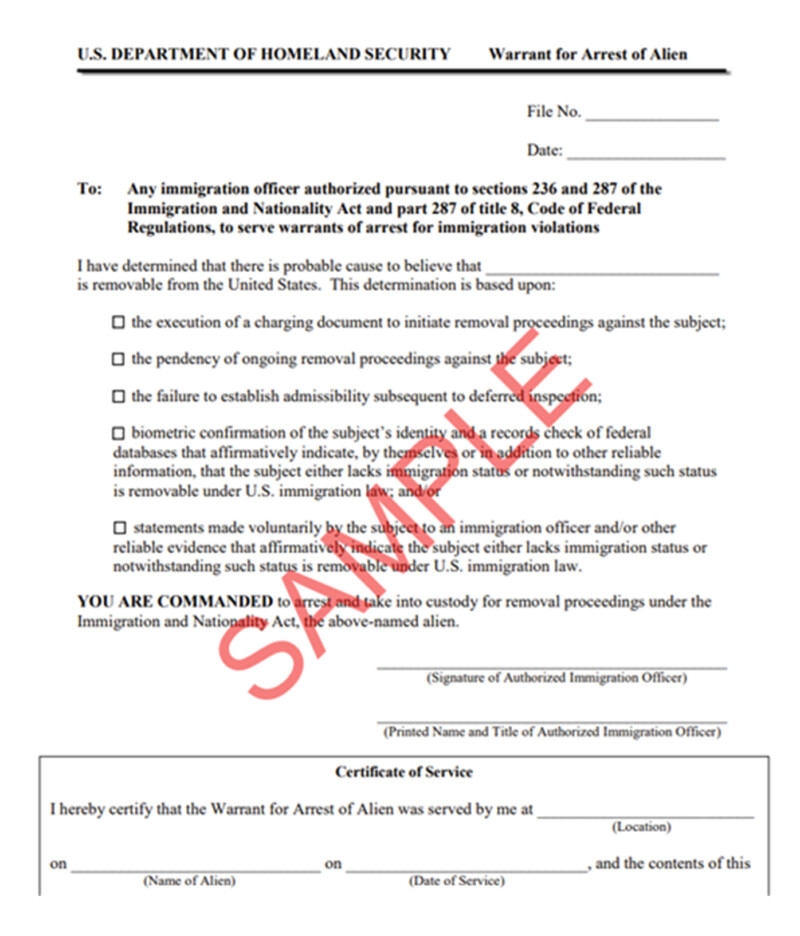

If ICE appears at a school, staff should be trained on how to respond, including admitting access only to areas that are open to the public, such as a parking lot or lobby; not providing ICE with direct access to any student; and not providing any information or records about a student unless a valid warrant or subpoena signed by a state or federal judge is presented. Here is an example of a warrant schools should disregard:

It is important to note that when schools comply with a valid subpoena, parents must be notified that they have done so.

Removing Language Barriers

On March 1, 2025, English was declared the official national language by Executive Order 14224, revoking a former order from 2000 aimed at ensuring that people with limited English proficiency could meaningfully access federal programs and services.

While the IDEA mandates translation only of “prior written notice," which, in Pennsylvania, consists of the NOREP and the notice of parent rights, Title VI of the Civil Rights Act of 1964 states that no person in the United States shall, on the grounds of race, color, or national origin, be excluded from participation in, denied the benefits of, or subjected to discrimination under any program or activity receiving federal financial assistance. As such, courts, the Department of Justice and the Department of Education interpret that to mean that that language barriers should not prohibit meaningful access to, and participation in, programs that receive federal assistance.

Good Policies

Translated forms and documents should be available if needed, such as IEPs, disciplinary notices, parental correspondence, and enrollment documents.

Access to interpreters should be given for parent meetings, IEP meetings, and the like (even if the translator is on speaker phone or video conference). Asking a student to translate for his or her family is not acceptable.

A language access plan should be established: give notice to parents that translation services are available, and have a policy whereby staff can identify the need.

Lack of funds in implementing the above is not a defense, as grants are available through the Every Student Succeeds Act, Title III. More importantly, denial of such services runs afoul of national origin discrimination.

United States Policies in Place that Afford Protection to Immigrants

1. Deferred Action for Childhood Arrivals (DACA)

DACA is a U.S. immigration policy that provides temporary protection from deportation and work authorization to eligible young people who were brought to the country as children. To qualify, applicants must:

- Have arrived in the U.S. before age 16 and resided continuously since at least June 15, 2007

- Be under the age of 31 as of June 15, 2012

- Have no serious criminal record, and

- Be enrolled in school, graduated, or served in the military honorably

DACA also allows individuals to apply for work permits, which had been previously renewable every two years, but in 2025 were reduced to one year. Despite the deportation protections outlined by DACA, there have been a number of instances in 2025 where DACA status was ignored by federal agencies, and the subjects were arrested and detained.

2. Temporary Protected Status (TPS)

For citizens of nations where there is a natural disaster, armed conflict, or other dangerous condition, TPS is a temporary immigration status that affords applicants protection from deportation and the opportunity to apply for a work permit or travel authorization. However, TPS does not lead to permanent residency or citizenship. Furthermore, when the dangerous condition is no longer an issue, TPS may be revoked and the individual must depart within 60 days or risk deportation. The present list of approved TPS nations includes the following: Burma (Myanmar), Cameroon, El Salvador, Ethiopia, Haiti, Honduras, Lebanon, Nepal, Nicaragua, Somalia, South Sudan, Sudan, Syria, Ukraine, Venezuela, and Yemen. However, the status of Burma, Cameroon, Ethiopia, Haiti, Honduras, Nepal, Nicaragua, South Sudan, Syria, and Venezuela will have this status revoked by or before the end of 2025.

3. Special Immigrant Juvenile Status (SIJS)

SIJS is a pathway to lawful permanent residency (Green Card) for undocumented children, but only if they were abused, abandoned, or neglected by one or both parents and cannot safely return to their home country. A state court must first find that they cannot reunify with parents and cannot safely return to their origin country.

4. Asylum

Applicants for asylum must have suffered persecution - or have a well founded fear of it - based on one of the following categories: race, religion, nationality, political opinion, or membership in a particular social group. There are two categories of asylum:

· Affirmative Asylum, where one proactively applies through the United States Citizenship and Immigration Services (USCIS) within one year of arriving in the U.S.

· Defensive Asylum, where asylum is requested as a defense against removal (deportation) during immigration court proceedings.

5. U Visa

A special nonimmigrant visa designed to protect victims of certain serious crimes who have suffered substantial physical or mental abuse and are willing to assist law enforcement in investigating or prosecuting the crime. The following prerequisites must be in place:

· The crime must be a violation of US Law

· The applicant must have suffered physical or mental harm

· The applicant must cooperate with law enforcement investigation and/or prosecution

Indirect victims also qualify for a U Visa, such as a child whose parent was murdered.

6. Violence Against Women Act (VAWA)

VAWA allows certain noncitizens who have experienced abuse by a U.S. citizen or lawful permanent resident (LPR) family member to apply for immigration relief without the abuser’s knowledge or consent. Eligible individuals include:

· Abused spouses and children of U.S. citizens or LPRs

· Abused parents of U.S. citizen sons or daughters

VAWA provides funds for domestic violence shelters and crisis centers, legal aid for survivors, and training for law enforcement and courts on gender-based violence.

Navigating the complexities of immigration policy and its impact on school districts requires a nuanced understanding of a shifting legal landscape, from evolving executive orders to foundational legal precedents that protect students' access to education, and the development of internal strategies to ensure the safety and well-being of all students.

Clients who have questions regarding issues discussed in this article, or any education law matter, should feel free to call us at 215-345-9111.